The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Generative AI for Proteins

This article was orginally written as a paid contribution to the Tribe AI Blog with the subtitle “For ML practitioners without biology or chemistry background.” I retain copyright.

Since Alphafold2 pushed machine learning into the biology spotlight, we’ve seen a flurry of activity around AI applied to structure and function of proteins. Following broad shifts in AI as a field, biologists are also creating purpose-built diffusion and transformer generative models. Instead of image and text, however, the medium is molecules and, increasingly, proteins. This short introduction to generative AI in a biological context is for the ML engineers getting started in the biological space with the desire–or perhaps mandate–to apply generative AI to biology problems.

Entering this field as an outsider–even as an experienced ML engineer–can be bewildering. Getting generative models to do what you want can be hard at the best of times, but applying to proteins presents extra challenges. Biology is a jargon-laden field, even by general scientific standards. Bioinformatics tools can be as unwieldy and arcane as the formats and standards they operate on. Getting lab scientists to agree on a machine-optimizable target can be tricky. Even routine experiments are notoriously hard to reproduce which makes ML pipeline iteration harrowing. And finally, while any lay person can sanity check the output of a text or image model, even protein experts might have to put in a bit of effort to distinguish plausible outputs from noise.

To help orient you, this guide will give you just enough grounding to:

- Grasp what a realistic task looks like

- Know what kind of model performance to expect

- Have a broad overview of the main models in use (ESM-2 and RFdiffusion), and

- Avoid some common pitfalls.

For the scientific side, I won’t assume anything more than a grade school understanding of chemistry–essentially, you need to already have an idea what a molecule is. Therefore, this guide will NOT:

- Help you find what kind of problems to solve. You will have to consult your expert colleagues.

- Teach you bioinformatics. Bioinformatics is manipulating biological data with a computer–for our purposes protein structures and sequences. This is a necessary and difficult skill to learn if you want to move beyond just running models with default settings on public databases. Fortunately, bioinformatics is a mature field and comprehensive tutorials exist.

- Exhaustively cover the literature. This is a big and fast-moving research area, but I’m just trying to help you get your bearings from an ML technical standpoint. If you want to delve into the research, consider this review or this review

- Teach you biology. Sorry about that! I will try to give you just enough understanding of what a protein sequence and structure are to understand what the models are trying to do. Consider the beautiful Machinery of Life to ignite a sense of wonder at the possibilities.

What are we trying to do?

Some examples from recent literature:

- Designing Efficient Enzymes An enzyme is a protein that can accelerate chemical processes. Making better ones can have huge economic or therapeutic impact.

- Designing new antibodies An antibody is an instrumental protein for the immune system, and designing new ones in new contexts can enhance existing medicine or create entirely new treatments.

- Managing fungal disease in plants Obvious agricultural implications.

However, documented applications of generative AI for proteins, let alone with experimental verification, are rare in the literature. To quote the fungal disease paper:

Despite its very strong results in protein binder design, RFdiffusion has been used in relatively few published studies at the time of this publication [Sept. 19, 2024]. Thus, there is limited information regarding best practices to use RFdiffusion…

This isn’t really a strike against RFdiffusion – it probably just means most work is being done commercially on proprietary or secret targets. After all, setting up a tightly-coupled team to implement state-of-the-art generative AI and do state-of-the-art laboratory experiments is not easy.

This is also an opportunity. Many articles, such as the enzyme and antibody papers above, are citing generative AI techniques aspirationally. That is, the authors already have pipelines to generate proteins but expect more advanced ML techniques could improve them. As someone breaking into the field, an exercise for you could be to take one of these papers with code available and try to add one of the models we discuss below.

Does it work?

Yes, but it’s a numbers game. Using state-of-the-art techniques, you can expect about 1 in 1,000 - 10,000 generated proteins to be good candidates for lab testing. This order of magnitude matches what I’ve seen in the literature and my experience.

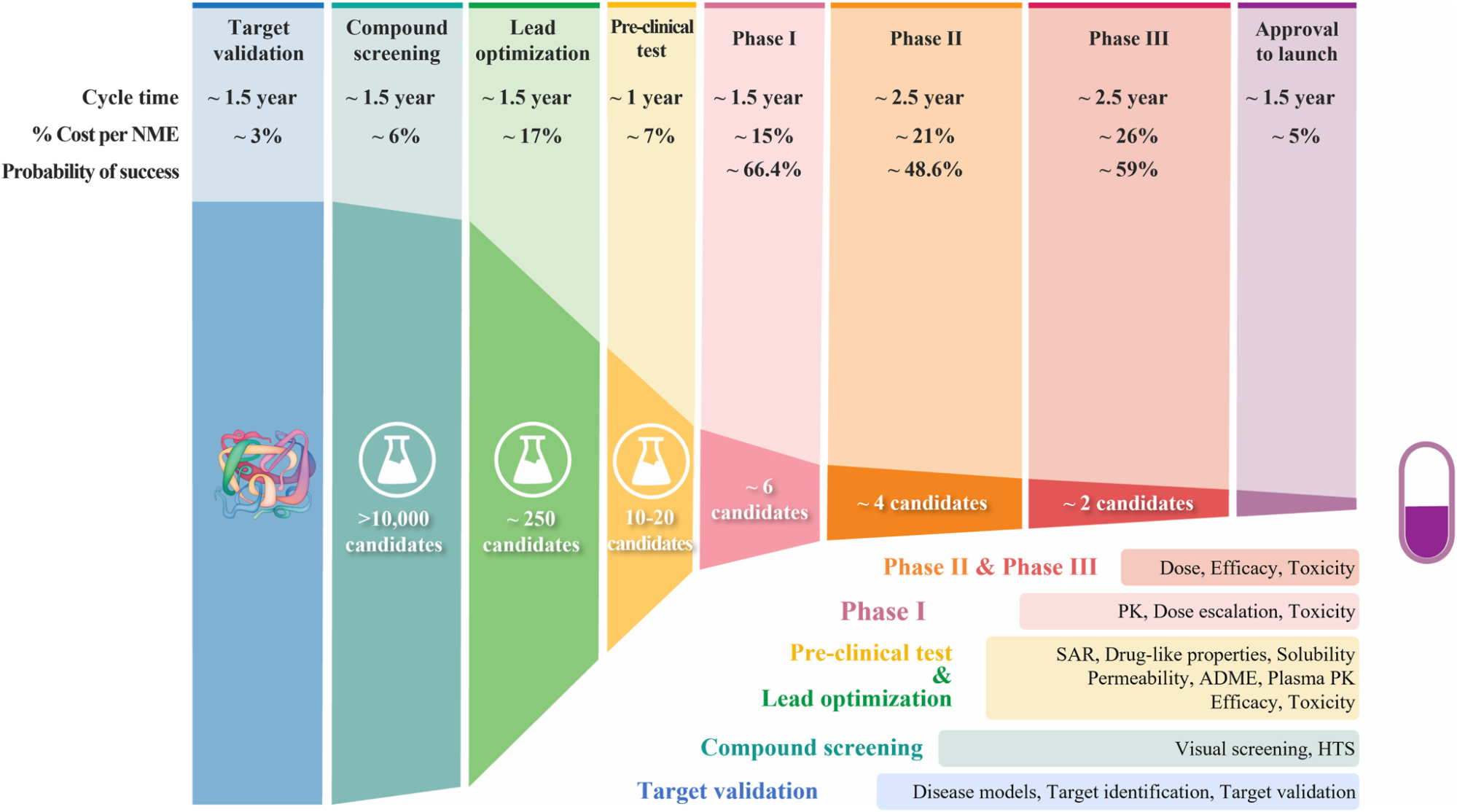

Although the examples above are not all pharmaceutical, when thinking about how to incorporate a computational effort into a discovery campaign it’s helpful to understand the drug discovery “pipeline.”

Every step serves to narrow down the possible molecules/protein sequences/whatevers with increasingly discerning but correspondingly more expensive lab experiments or trials. The goal of any ML model, generative or otherwise, or indeed any computational effort is to replace or narrow the scope of expensive and time-consuming lab experiments and find promising proteins or molecules more quickly. This applies whether you’re searching for new drugs or new enzymes.

Understanding where your generative AI effort fits into your pipeline is crucial. In particular, understanding what kind of lab experiment will be used on your result should inform your strategy: can your lab reasonably test 100 sequences or 10,000? If it’s only 100, you need to be a lot more sure about your generated results.

Unfortunately, generative models so far available are not well-suited to generating protein sequences with specific properties by themselves. They are great at generating plausible sequences and structures, but unlike image and NLP models, it can be difficult to evaluate whether it’s junk or not. We’ll discuss some ways to deal with this below.

Sequence and Structural models

First an extreme crash-course on protein basics, with apologies to any biologists reading.

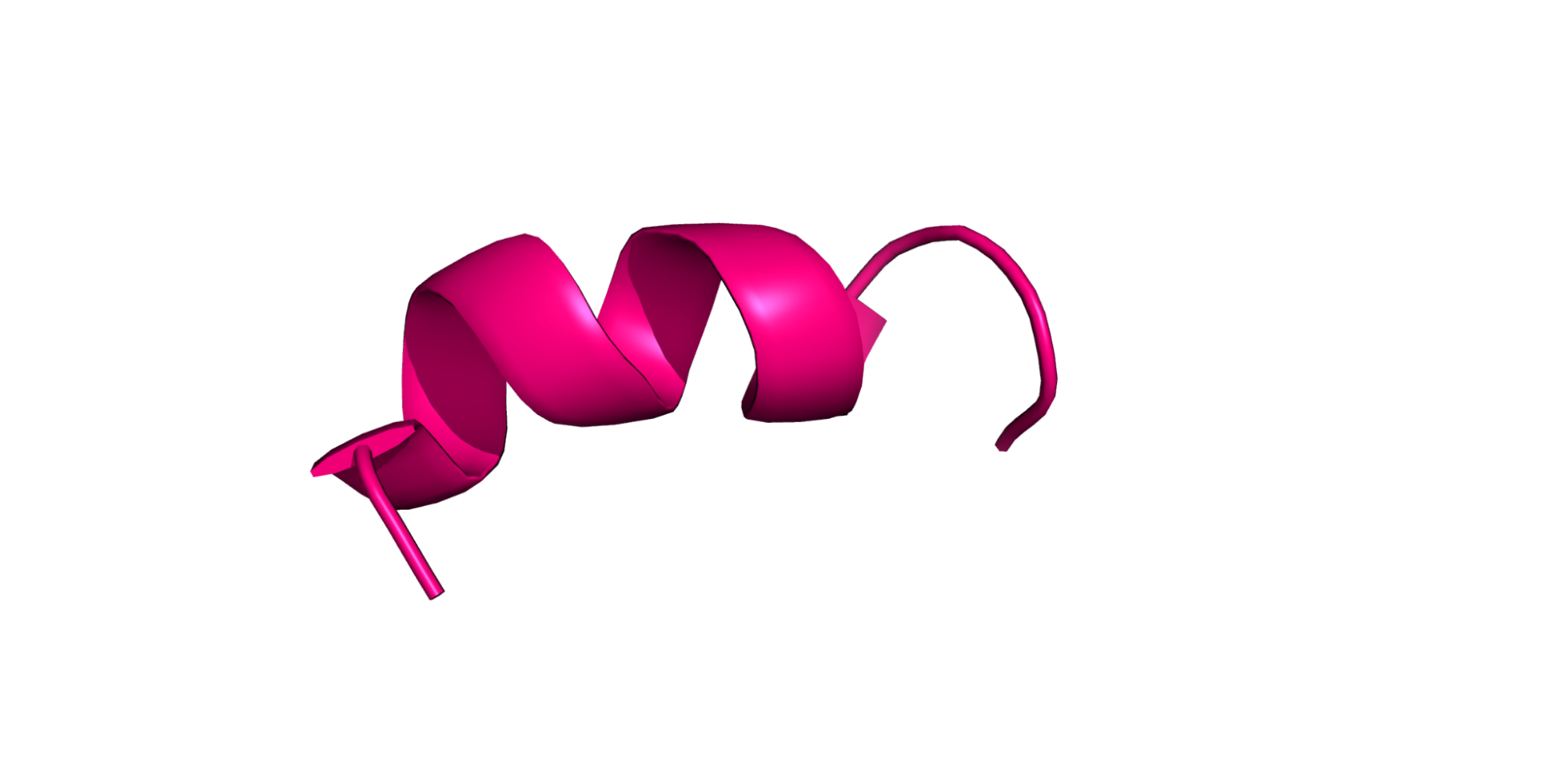

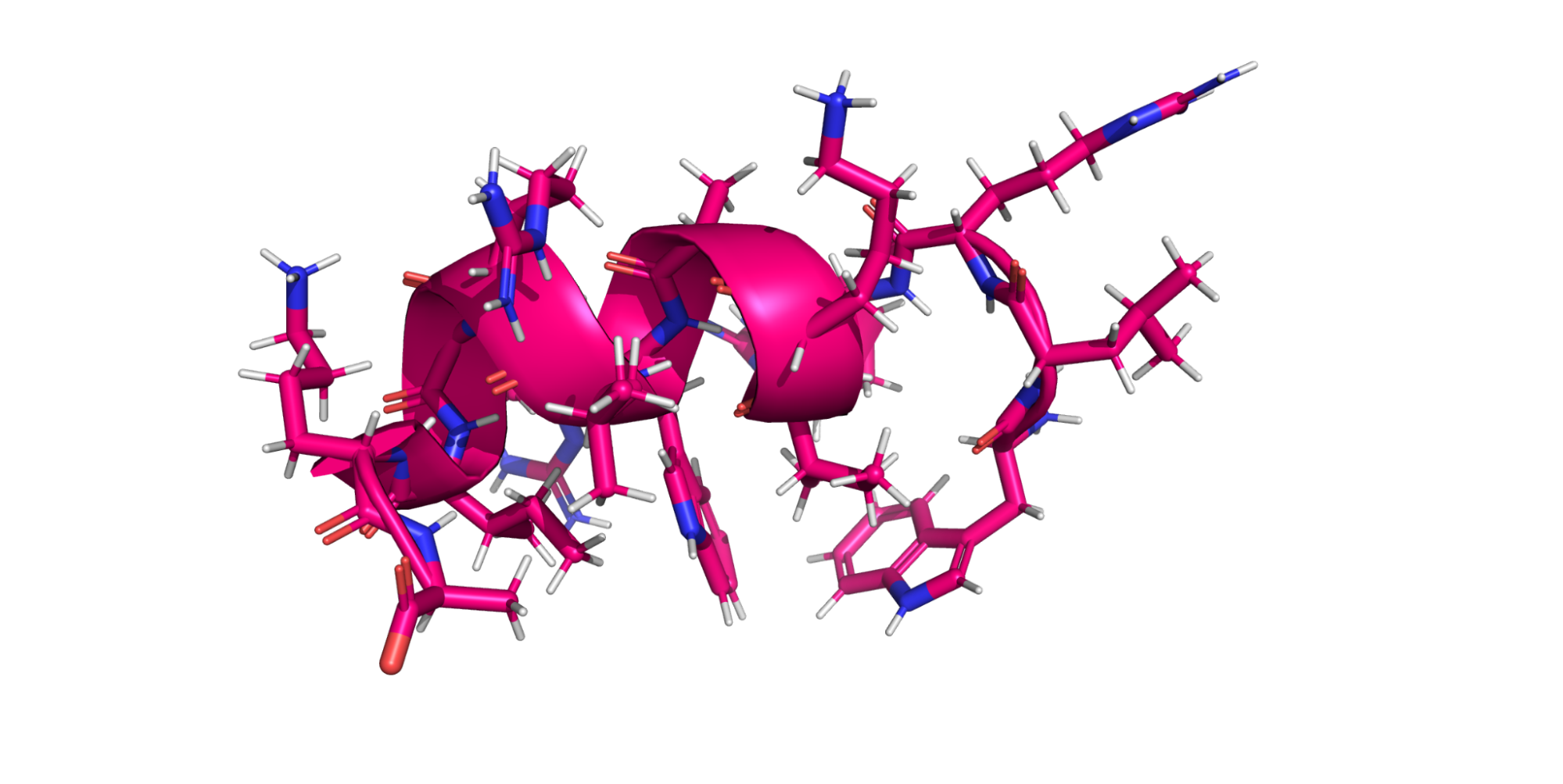

For our purposes, a protein is a chain of amino acids. Amino acids are small molecules, which when linked together in a chain, form a protein. The order of the amino acids is the protein sequence, and the 3D arrangement of the atoms in the linked amino acids is the structure. The sequence is usually recorded as a string of capital letters.

Each amino acid may also have flexible or free-moving parts called side chains, which are all of the stuff sticking off the ribbon in the figure above. These side chains are usually crucial for determining the kinds of interesting properties you will be looking for.

Obtaining the structure of a protein is much harder than obtaining its sequence. There are many, many more determined sequences than structures: at least several orders of magnitude more. So while the sequence alone hides a lot of information, the sheer volume of sequence data cannot be ignored.

Accordingly, there are two families of generative protein models: sequence and structural. Sequence models will be very familiar to ML practitioners as these are transformer models with amino acids as tokens, which take advantage of the huge amount of sequence data available. Structural models work on the 3D atomic structure of the protein.

Despite the relative shortage of structural data, the field seems to be eschewing sequence models in favor of more powerful structural models.

ESM-2

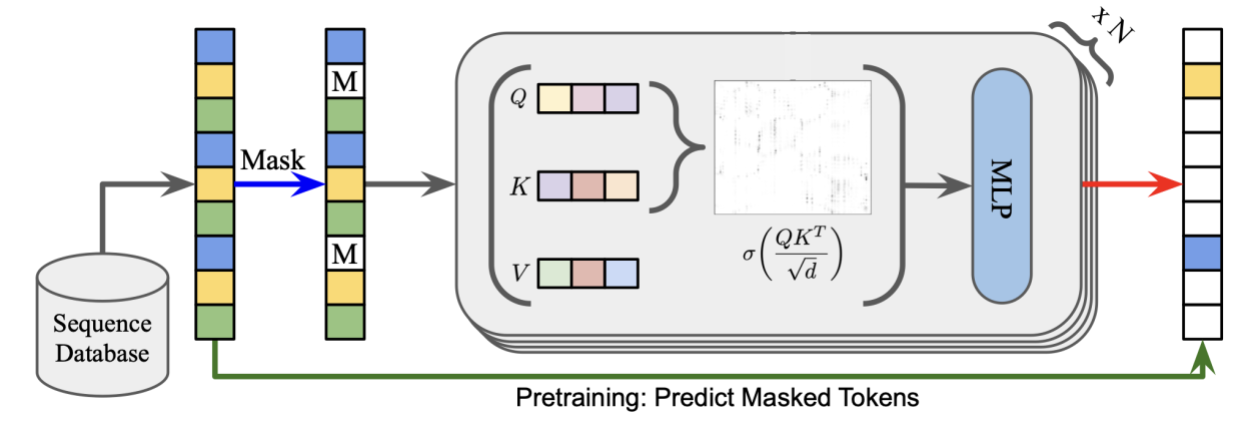

ESM-2 is a transformer model developed at Facebook. Initially used only for protein sequence generation, it was later expanded to 3D structure modeling. Conceptually this is very similar to BERT or GPT style training. A corpus of protein sequences, with amino acids as tokens, is trained autoregressively to predict missing parts of the sequence.

Although ESM-2 can predict structure, in my experience it’s used primarily to create embeddings for downstream tasks or clustering rather than direct sequence or structure generation. However, fast inference means this remains an important part of the toolkit.

RFdiffusion

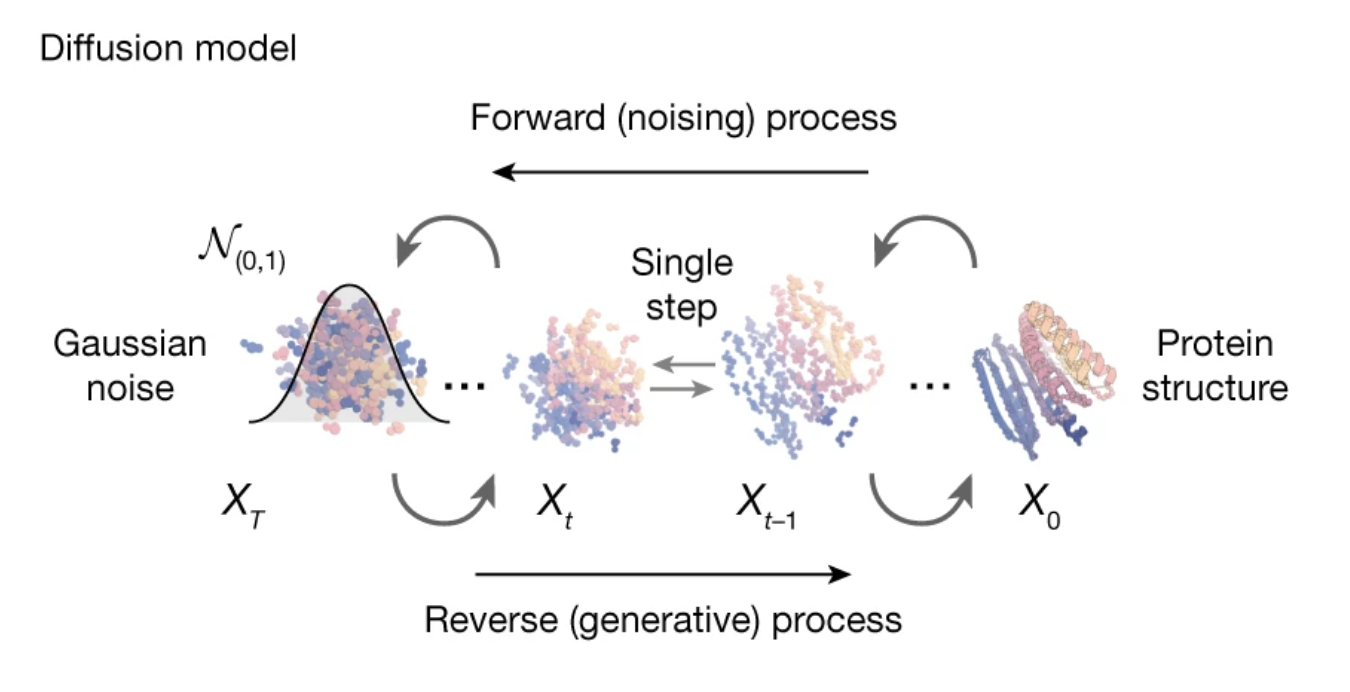

The current standard generative model for protein structure generation is RFdiffusion, or rather RFdiffusion plus ProteinMPNN. RFDiffusion, as the name suggests, is a diffusion model that noises and denoises a protein backbone to come up with a new structure. What is a backbone? Simply put, generating the chain without specifying the amino acids. Afterwards, a separate model called ProteinMPNN generates the missing sequence. This pipeline can generate entirely new proteins or parts of existing proteins.

Selecting which generated structures/sequences to use can be a challenge. The RFDiffusion authors suggest running a structural model from the generated sequence (in their case, Alphafold2) and seeing how closely it aligns with the RFDiffusion+ProteinMPNN generated structure. The rationale being that if the two models are in agreement, the structure is more likely valid. This makes intuitive sense and indeed seems to work well for filtering out “bad” structures, but not so great for picking unusually good ones. Scoring the generated structures against AF2 has the added disadvantage of adding another expensive step to an already computationally heavy pipeline.

A realistic example

In the paper De novo design of high-affinity binders of bioactive helical peptides, the authors use an RFdiffusion pipeline to generate binders to a particular kind of hormone. This paper is worth reading because it comes from the same group that built RFdiffusion and describes a realistic ML + experiment setup. Some highlights:

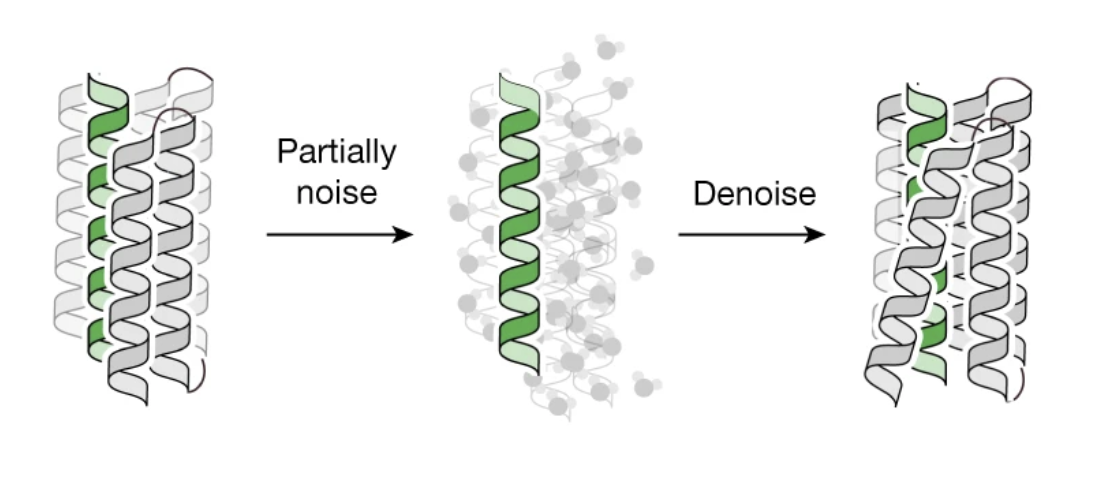

- Start with pre-designed structures While most protein generative models do a template search of some kind, sometimes you’re better off just generating unoptimized structures with a non-ML program that are near to what you expect. These can be used as a starting point for diffusion. In this work–see the first two subsections under “Computational Methods”–a scaffold library is generated to be used as a base for the generative model, and RFdiffusion’s “partial diffusion” mode is used to generate plausible binders from this starting point.

- Carry out multiple rounds However you inspect the results of your generative models, these results can be used as the inputs to another generative round. See “Sequence threading to generate peptide binders” under Computational methods.

- Combine with other models In this case AF2 for structure verification and AF2 Hallucination to enhance binding.

The authors also kindly give numbers of structures they generate at each step: e.g. “2,000 partially diffused designs were generated for each target,” which gives you a sense of scale for the computational experiment.

Challenges

Doing better than nature

While generative models like RFDiffusion are astonishing, they have a tendency to generate plausible alternatives that are “as good” as a naturally occurring protein for your desired property or function. While this might be sufficient for some applications, often we are trying to do better. In this case you might need to filter or rank your generated structures according to some other simulation or model. Fine-tuning also comes to mind, but be careful not to reach for a risky ML solution when a computational biology solution might already exist.

PDB file format

The standard format for storing protein structures digitally is the Protein Data Bank (PDB) format. It was first designed in the 70s and is showing its age despite updates. Be aware that many programs will save PDBs with only partial adherence to the standard. For working with PDBs, I suggest PyMOL for visualization and the biopython suite for processing them in your pipeline. Fortunately, most groups which release new models also include an example data pipeline, though you will often still need to fill in gaps.

Specificity

Especially in therapeutic use cases, generating a promising new protein is not enough. You have to worry about how it interacts with other proteins and molecules that it might encounter. Simply put: a cancer-killing treatment is less useful if it also is patient-killing. Try to understand if this could be an issue in your problem space.

Working with scientists

I’m a scientist myself, but this can still be frustrating. They will treat generative AI like the result of a simulation even though intellectually they understand the difference. They’re also famously skeptical, so be prepared for pushback no matter how good the results.

The biotech industry

It’s really secretive. This will be a challenge especially if you have to work with groups outside of your organization.

Looking forward

As we discussed above, the biggest outstanding problem for generative AI in biology is getting generated proteins to have specific properties. New models promise to push generated structures to do just that: AlphaFold3 and ESM-3. However both have restrictive (non-commercial) licenses, and for AlphaFold3, the code is not even available. As such, I can’t really recommend them yet.